- Home

- Seymour I. Schwartz

Cadwallader Colden

Cadwallader Colden Read online

Published 2013 by Humanity Books, an imprint of Prometheus Books

Cadwallader Colden: A Biography. Copyright © 2013 by Seymour I. Schwartz. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Cover design by Liz Scinta

Inquiries should be addressed to

Humanity Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228–2119

VOICE: 716–691–0133

FAX: 716–691–0137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Schwartz, Seymour I., 1928-

Cadwallader Colden : a biography / by Seymour I. Schwartz.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61614-853-9 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61614-854-6 (ebook)

1. Colden, Cadwallader, 1688-1776. 2. Lieutenant governors—New York (State)—Biography. 3. New York (State)—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775—Biography. 4. United States—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775—Biography. 5. New York (State)—Intellectual life—18th century. 6. United States—Intellectual life—18th century. 7. Intellectuals—United States—Biography. 8. Scientists—United States—Biography. 9. Royalists—United States—Biography. I. Title.

F122.C6872 2013

973.2—dc23

2013028690

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Chapter 1: Before Taking Root: 1688–1718

Chapter 2: The New New Yorker: 1718–1728

Chapter 3: A Country Gentleman Remains Focused on Colonial Concerns: 1729–1738

Chapter 4: Concentrated Correspondence and Evolving Enlightenment: 1739–1748

Chapter 5: Continuity and Change: 1749–1758

Chapter 6: Political Peak and Reputational Nadir: 1759–1768

Chapter 7: An Octogenarian: 1769–1776

Chapter 8: Epilogue and Legacy

Endnotes

Papers and Publications

References

Index

To Dennis Carr, a staff member of the Miner Library of the University of Rochester Medical Center, whose assistance over the past several years was invaluable. To Gianna Nixon for her graphic assistance.

The second half of the year of 1776 witnessed several historic events in British Colonial North America. On July 2, the thirteen colonies declared their independence from Great Britain. Two days later, the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Congress in Philadelphia. On the same day, the British fleet was sighted off New York. On September 15, the British occupied the City of New York, which George Washington and his army had just abandoned, moving north to encamp at Harlem Heights. On September 21, about one-third of lower Manhattan was destroyed by the Great New York Fire of 1776. Also on September 21, Nathan Hale, a spy in the Continental Army, was captured near Flushing Bay in Queens, New York, behind enemy lines. He was hanged the next day at the Park of Artillery (current 66th Street and Third Avenue in Manhattan). Nathan Hale was immortalized by the statement he issued before the hanging: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” On the day before Nathan Hale's capture, also in Flushing, not far from where the capture occurred, the life of an eighty-eight-year old man came to a peaceful end and his name drifted into obscurity.

The name of that man, Cadwallader Colden, brings into focus an individual who served the Colony of New York for over a half century, longer by far than any of his contemporaries. Throughout that period, he remained unwaveringly devoted to the British monarchy. As such, he became one of the most reviled New York colonial figures. His name also identifies a physician, scientist, botanist, ethnographer, and philosopher; a savant, who was deemed by colonial intellectuals as the most knowledgeable individual in all of the land. He shared an interest and dialogue with three other colonial physicians, who were similarly notable for diverse contributions beyond the realm of medicine.

Colden generated a large corpus of correspondence with the most notable scientists and thoughtful men, both in America and on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. This is evidenced by a nine-volume publication by the New York Historical Society containing his correspondence. Yet, with all his recognized accomplishments and contemporary visibility, the name of Cadwallader Colden does not appear in the famous Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, with whom Colden was engaged in an extensive correspondence. Their letters speak to a mutual high regard. Nor has Colden's long, productive, and influential life been the subject of a published biography, with the exception of a rarely read 1906 doctoral thesis1 and a recent addition to Contributions in American History.2 Both of these works essentially compartmentalize Cadwallader Colden's intellectual pursuits.

What has been lacking is a historical correlation between Cadwallader Colden's personal and political life with his many and varied intellectual pursuits. As a husband and father, he maintained constant concern for his large family, whose members reciprocated with admiration and strong emotional ties. The results are apparent in a consideration of the family's genealogy. His positive and praiseworthy familial relationships contrasted with his public persona, which was characterized by the inability to relate to political associates. Compromise and compassion were absent from his political lexicon.

His dedication to intellectual enquiry was unique for his position and location, but it was tainted by a desperate need for recognition and accolade. He was devoid of an appreciation of his intellectual capabilities, consequent to the absence of a firm basis in mathematics. Although he gained respect, it was never sufficient. The name of Cadwallader Colden, which could have become a beacon in the colonies and persisted for ages, has been diminished and erased with time. The sequence of life for arguably the most notable New York colonist was famed, flawed, forgotten!

Counter to the usual course in which the Scotch-Irish immigrants to colonial America joined in with rebellious factions, Cadwallader Colden (fig. 1) never diverted from his dedication to British rule and his obligation to the Crown. This can be ascribed, in part, to his genetic and acquired conservatism related to the early parental influence during his youth. Colden was born in Ireland on February 7, 1688,a to Scottish parents, the Reverend Alexander Colden and his wife, Janet Hughes. Alexander Colden had received an MA from the University of Edinburgh in 1675, and, in 1685, he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister. He was initially assigned to a parish in Enniscorty, County Wexford, Ireland, where Cadwallader was born. A year after Cadwallader's birth, his father was transferred to the Presbytery of Duns, Scotland, about thirty miles from Edinburgh. His parents would remain at that post for the rest of their lives.1

In Alexander Colden's final letter to his son,2 dated August 5, 1732, in which it is noted that Cadwallader's mother died on September 23, 1731, Cadwallader's father proudly reported that, at the time, he had the distinction of being the oldest minister in the Church of Scotland. In that letter, as in all of his correspondence, Cadwallader Colden's father's rigid religiosity is evident. The narrative of each letter assumed a ministerial tone as the pen issued forth pages of sermonizing directed at his son. It was as if the son was a member of the father's congregation.

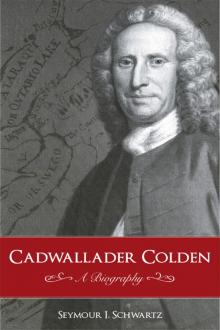

Figure 1. Cadwallader Colden. Portrait of Cadwallader Colden by John Wollaston (The Younger), 1749–17

52. Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Grace Wilkes, 1922 (22.45.6). All rights reserved, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cadwallader's youth was spent in a bucolic environment, not far from the east coast of southern Scotland. As a young teenager, he was sent to the University of Edinburgh in preparation for following in his father's ministerial footsteps. Cadwallader was admitted in 1702 and matriculated in February 1703, entering as a second-year student because of his proficiency in Latin and Greek.3

As part of his studies, Cadwallader was exposed to botany, which was an integral part of the curriculum. The subject had been added to the roster of courses at the University of Edinburgh in 1676. At that time, it was stated: “[C]onsidering the usefulness and necessity of encouragement of the art of Botany and planting of medicinal herbs, and that it were for the better flourishing of the College that the said profession be joined to the other professions, they appoint Mr. James Sutherland, present Botanist, who professes the said art; and upon consideration aforesaid, they unite, annex, and adjoin the said Profession to the rest of the liberal sciences taught in the College, and recommend the Treasurer of the College to provide a convenient room in the College for keeping books and seeds relative to the said Profession.”4 The subject, in which Cadwallader would maintain a long-term interest, was introduced to him by Dr. Charles Preston, the author of Hortus Medicus Edinburgensis.5

Colden graduated with an MA from the University of Edinburgh in 1705. Stimulated by his study of the sciences, including Newtonian science and general physics, Cadwallader forsook his father's plan and elected to study medicine in London, where, within a period of five years, he completed a course in anatomy with Doctor Ariskine and a course in chemistry with Mr. Wilson, both distinguished in their professions.6 As Colden later confessed in a letter to the Swedish botanist Peter Kalm, he was unable to establish a medical practice that would sustain him in London, and so in 1710, he accepted the invitation of Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, his mother's widowed and childless sister, to join her in Philadelphia, at the time, a community with less than three thousand inhabitants. There, he planned to pursue his medical career while assisting his aunt in her mercantile business.7

The business, which concentrated on trade with the West Indies, took Colden to Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua, and St. Kitts. The bills of lading of the trade chronicled shipments of the two-way traffic that was dominated by sailings between Philadelphia, the busiest colonial port at the time, and, mainly, Barbados, the largest of the British colonies in the Caribbean Sea. Sugar, rum, and molasses were shipped from the islands, while bread, flour, meat, dry goods, and Madeira wine were sent from North America to the West Indies. One consignment from Colden in Philadelphia includes a “Negro Woeman & Child.” She was described as “a good House Negro understands the work of the Kitchen perfectly & washes well. She has a natural aversion to all strong Liquors. Were it not for her Allusive Tongue her sullenness & the Custome of the Country that will not allow us to use our Negroes as you doe in Barbados when they Displeas you I would not have parted with her.”8

In 1715, Colden interrupted his work in Philadelphia and traveled to Great Britain, where, that year, he married Alice Chrystie (fig. 2), the daughter of a Scottish minister in Kelso, about twenty miles from where he had spent his own youth. Alice was two years Cadwallader's junior and the sister of his friend and classmate at Edinburgh. Colden and his wife would eventually parent ten children, eight of whom would survive infancy. Colden's visit home coincided with the First Scottish Rebellion, known as “The Fifteen,” in which there was an attempt to return the Stuarts to the throne. In a subsequent letter, written in support of Colden, in order to counter the criticism that he was a Jacobite rather than a staunch unionist, it was pointed out that, “on the News of McIntoshes Landing on the South Side of the First of Edinburgh he [Colden] brought upward of Seventy Men from the Parish where his Father lives and continued with your Lordship [the Marquis of Lothian] under Arms at Kelso several days.”9

Figure 2. Alice Christy Colden. Portrait of Alice Christy Colden by John Wollaston (The Younger), 1749-1752. Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Grace Wilkes, 1922 (22.45.6). All rights reserved, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During that 1715 trip, which was the last time Colden returned home, he met Edmund Halley, the famous astronomer whose name was attached to the comet, the orbit of which he had defined. Colden visited the Royal Society, which received and published his first scientific paper, “Animal Secretions.”10

The married couple arrived back in Philadelphia in 1716. On his return, Colden concentrated to a greater extent on his medical career. He purchased a barometer and thermometer, from Edinburgh and sent for “any thing that is new in Medicine Mathematics History or Poetry, including the last edition of Newton's Optics and Dr. Gregory's astronomical tables.”11 Among the medical texts ordered by Colden were: Le Clerc Histoire de la Medicine, Hovius de Circulari Humoum, Motie in Oculis, Nuck Operationes et Experiment Chirurg, Wepfer Historia Cicutae Acquaticae, Banister Herbarium Vorgineanum, Artis Medice Principles published by Borheowe, Ruyschs Observation.12 He also ordered a variety of drugs from an apothecary in addition to mortars, crucibles, and Glyster pipes.13

Colden, as a formally trained physician, was a member of a distinct minority. William Smith, Jr., in the first volume of The History of the Province of New-York, covering a time period that ended in 1732, wrote: “Quacks abound like Locusts in Egypt, and too many have recommended themselves to a full Practice and a profitable Subsistence. This is the less to be wondered at, as the Profession is under no Kind of Regulation. Loud as the call is, to our Shame be it remembered, we have no Law to protect the Lives of the King's Subjects, from the Malpractice of Pretenders. Any Man at his Pleasure sets up for Physician, Apothecary, and Chirurgeon. No Candidates are either examined or licensed, or even sworn to fair Practice.”14

Only one of Boston's ten practitioners had a foreign medical degree in 1720, and only one of nine Virginia physicians of the eighteenth century had attended medical school.15 William Douglass, the one Boston physician with a foreign medical degree, in the 1750s wrote: “by living a year or two in any quality with a practitioner of any sort, apothecary, cancer doctor, cutter for stone, bone-setters, tooth-drawer, &c. with the essential fundamentals of ignorance and impudence, is esteemed to qualify himself for all the branches of the medical art, as much or more than gentlemen in Europe well born, liberally educated (and therefore modest likewise) [who] have travelled much, attended medical professors of many denominations, frequented city hospitals, and camp, infirmaries, &c. for many years.”16 At the time of the American Revolution only 5 percent of medical practitioners held a recognized medical degree.17

An eighteenth-century Virginia practitioner, who had trained under the apprenticeship system, countered that “those self swollen sons of pedantic absurdity, fresh & raw from that universal asylum of medical perfection, Edinburgh,…. [who] enter with obstinate assurance upon the old round of obsolete prescription, which their infallible masters taught them, &, like the mule that turns aside for no man, push on in their bloody career till the surrounding mortality, but more especially the danger of their own thick skulls, brings them to pause, & works in them a new conviction.”18

Colden is credited with the first attempt to establish a systematic course of medical lectures in the colonies.19 He directed his proposal to James Logan, an influential Philadelphia politician with an interest in science, including botany and Newtonian physics, who was the cousin of Colden's wife. Logan was described as “the region's most influential statesman, its most distinguished scholar, its respected—though not its most beloved—citizen.20 Logan had invited Colden to assist him in using a telescope to observe an eclipse of the sun in order to compare observations made by astronomers in England. As is noted in a letter by James Logan, written May 1, 1717, in addition to Colden's educational proposal, he requested that an arrangement be est

ablished in which he could be compensated for taking care of the poor.

He [Colden] came to me one day to desire my opinion of a proposal to get an act of Assembly for an allowance for him as physician for the poor of this place. I told him I thought very well of the thing, but doubted whether it could be brought to bear in the House. Not long after R. Hill showed me a bill for this purpose, put in his hands by the Governor, with two further provisions in it, which were, that a public physical lecture should be held in Philadelphia, to the support of which every unmarried man above twenty-one years, should pay six shillings, eight-pence, or an English crown yearly, and that the corpses of all persons that died here should be visited by an appointed physician, who should receive for his trouble three shillings and four-pence. These things I owned very commendable, but doubted our Assembly would never go into them, that of lectures especially.21

In 1718, Colden's life changed rapidly and dramatically. The change would provide for him the platform for his political performance and the opportunity to satisfy his intellectual curiosity. It began when Colden casually visited New York and, in accordance with protocol, called upon the governor of the province, Robert Hunter. Hunter was a fellow Scot, who had apprenticed to an apothecary but ran away and joined the army. He rose in the ranks, married a woman of high status, and served under the Duke of Marlborough until 1709 when he was made governor of New York. Hunter was an intellect, a classical scholar, linguist, poet, amateur scientist, and a member of the Royal Society of London. Hunter was immediately impressed with Colden's potential as an aide in the governance of the province of New York.

Hunter sought an endorsement for Colden and, in response to Colden's request for a recommendation to Hunter, Logan wrote that it was, “too much like a man's desiring his wife to speak on behalf of another woman…. My heart goes against my head” and if “Colden were doomed to leave Philadelphia, I should wish him at New York, and can say no further.”22 About two weeks after Colden's visit to New York, he received a letter from Governor Hunter offering him the position of surveyor general and master in chancery. Colden immediately accepted and moved with his family to New York.

Cadwallader Colden

Cadwallader Colden